Introduction

The concept of software architecture started in the 1960s, during the time when the idea of object-oriented programming (OOP) was introduced. Before that, programming was low-level and written in assembly language. In the 1970s, higher-level programming like C/C++ started to gain popularity, programmers began theorising about how to structure software, exploring ideas around modularity and introducing different architectural styles. Some of the most well-known architectures include monolithic, microkernel, and microservices.

Diagramming became an essential engineering practice for designing software. It started with a modelling language called Unified Modelling Language (UML) for object-oriented programming, then evolved to include more flexible approaches, like ArchiMate for enterprise architecture, and C4 Model for modern software systems. Teams in non-enterprise environments often default to pragmatic approaches for communicating architecture, using simple boxes and arrows as the basis for diagramming.

Purpose of software architecture

Some engineers perceive architectural diagramming as a secondary piece of documentation that they optionally produce and the intended audience is their teams only. This is a common misconception that undervalues the real purpose of software architecture. In reality, architectural diagramming is:

- Not secondary: Designing architecture is as important as writing code that runs the system.

- Not optional: it should be defined before building a new system or implementing a feature as it clarifies dependencies and interactions.

- Not only: Architecture diagrams also serve the wider organisation and other stakeholders by documenting the key architectural decisions to maintain the system.

Martin Fowler, Chief Scientist at Thoughtworks, is one of the most influential people in software architecture. He emphasised the importance of software design through his books like Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture and Refactoring. In a well-known email exchange with Ralph Johnson, he defined architecture as the shared understanding that the expert developers have of the system design. Check out his 15-minute talk on YouTube where he explains what architecture is and why it matters.

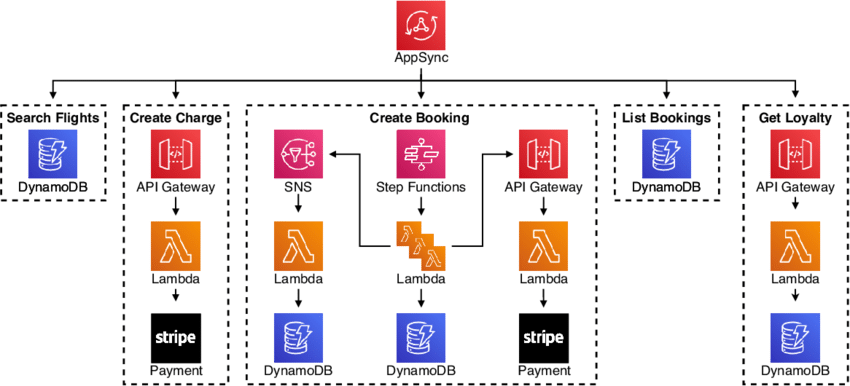

Fundamentally, software architecture defines the organisation of a system: how components communicate and, when grouped together, ultimately deliver value to users. Think of it as the difference between a booking system (architecture) versus an individual payment (component within architecture). Here is an example of an AWS architecture below:

Source: https://shorturl.at/cp8U0

To document software architectures, diagramming is an important exercise for visually representing component relationships and communicating architectural decisions clearly. That’s why system design interviews are widely used to assess a candidate’s ability to think architecturally and communicate trade-offs when designing scalable systems.

Common Mistakes

Some mistakes people make when designing software architectures are:

1. Focusing on too much detail.

Some engineers tend to approach diagramming as a way to enumerate every component and all of its edge cases. For example, say there is a web service that calls multiple endpoints to complete a specific flow (e.g., a checkout flow). Some engineers will want to highlight this flow in their architecture with all the edge cases to make it comprehensive. However, that is not the goal of the architecture, that belongs in an activity diagram. The purpose of a software architecture diagram is to highlight the current state of the system and the key decisions behind the design.

2. Serving all stakeholders with a single diagram.

Each type of audience has a requirement from the architectural diagrams. Product and design want a brief, high-level understanding of how the major pieces fit together. Engineers want to see more than high-level, they want to understand the technical details and decisions made behind each component. For example, product managers might want to understand the mobile app integration project through the Context layer or Container layer of the C4 model, while engineers need more details like the authentication flow in the Component layer.

Even with AWS diagrams, architecture can be split into layers of abstraction similar to the C4 model. Product teams can view high-level diagrams that explain the customer onboarding process for their new SaaS product (e.g., user dashboard, analytics, or named business services), while engineers can reference low-level architecture diagrams that focus on networking components (such as VPCs, subnets, and data access patterns) and services (such as EC2 and ECS) that run the infrastructure.

A single diagram cannot effectively serve all audiences, it will either be too simplistic or too complex for at least one group.

3. Mixing levels of abstraction.

Mixing levels of abstraction is a common trap in architecture diagramming. Some engineers tend to show high-level components like web services or datastores alongside lower-level details like OS processes or network connections, often making it unclear what the viewer should focus on or what is important. A better approach is to be intentional about the level of detail you’re presenting. High-level diagrams should communicate the overall system structure and architectural decisions, while separate, detailed diagrams can expand on specific modules or flows. This way, each diagram has a clear purpose and is easier for its intended audience to understand. A good way to avoid mixing abstractions is to follow a structured approach like the C4 Model.

Future of software architecture with AI

TL;DR: a “vibe-diagramming” phase will soon disrupt the industry, but the need for software architects will still exist.

Current LLMs like GPT-5.1, Gemini 3 Pro, Claude Sonnet 4.5 are the state-of-the-art models. They excel at generating production-quality code, interpreting large contexts (e.g., monorepos), and building deep understanding and reasoning within enterprise systems. However, they still struggle with nuanced design and architectural decision-making (try to ask it to design a Ticketmaster). For now, LLMs can generate simple language-based diagrams like Mermaid.js and help interpret existing architectures, but designing and maintaining the overall architecture of a complex system still requires human expertise.

The past few years have been a disruptive shift to the software engineering industry, with predictions that AI would replace software developers entirely. That hasn’t happened. Human involvement remains essential for strategic thinking and problem-solving. We believe the same pattern will apply for software architects.

AI will eventually transform the software architecture domain, but the fundamentals won’t change. Even as LLMs improve at diagramming, software architects will still be needed for understanding business constraints, making trade-offs, and aligning technical decisions with business goals. The future with AI will be an accelerator for architects, not a replacement.

For interpretation, you can explore architecture diagrams by querying an MCP server (e.g., see IcePanel’s MCP). However, designing or maintaining architectures with AI is still in its early stage. Software architects can use AI tools to interpret architecture, but not yet to create it.

Conclusion

Software architecture diagramming has evolved from early theories of software design in the 1960s and formal modeling languages like UML to the flexible, pragmatic approaches that serve modern development teams today. The core purpose remains unchanged: to visually communicate how systems are organised, document key architectural decisions, and create shared understanding across teams.

While we’ve discussed common mistakes to avoid and good practices to follow, the landscape is shifting as AI tools begin to enter the architectural workflow. The question isn’t whether AI will impact how architects diagram and design systems, but rather how architects can best leverage these emerging capabilities to enhance their work.

As AI tools continue to advance, they’ll augment architects’ capabilities in interpreting and generating diagrams, but human involvement will remain necessary. The future belongs to architects who leverage AI as a design assistant while maintaining their role as strategic technical leaders who understand business constraints, evaluate trade-offs, and align technical decisions with organisational goals.

If you enjoyed this piece, check out our related post on how AI is redefining the role of a software architect: https://icepanel.io/blog/2025-07-21-how-ai-is-redefining-the-role-of-a-software-architect